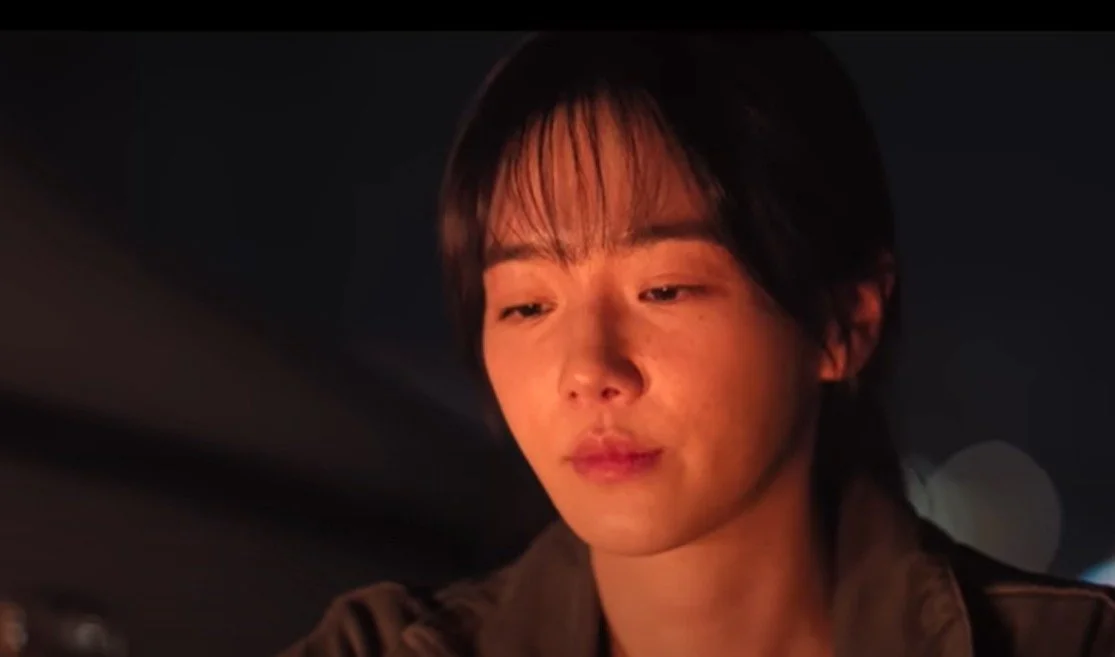

“Kang No-eul” is a North Korean defector in Squid Game 3, who escapes to South Korea, only to learn through a broker that the child she was forced to leave behind may still be in China. While Squid Game is a television drama, Kang’s story and the anguish of separation echo a painful reality faced by many North Korean women under our care at Crossing Borders. These mothers, who fled desperate situations in China, often had no choice but to leave their children behind.

Now safe in South Korea – free from the constant fear of being trafficked, arrested or forcibly repatriated to North Korea, where they would likely face imprisonment, torture or worse – they cling to fleeting connections with their children through video calls and text messages over WeChat, with no realistic hope of reunion. Each time they speak about their children, the sorrow is palpable, often bringing about tears.

THE PLIGHT OF STATELESS CHILDREN

Children of North Korean refugees at a retreat with a counselor from Crossing Borders

While exact figures are difficult to confirm, research suggests there may be up to 30,000 children born to North Korean mothers and Chinese men across China. Many of these children grow up stateless, without a hukou (household registration). Out of fear of exposing their undocumented mothers and risking her repatriation, many parents avoid registering their child. However, without hukou, they effectively have no legal existence – excluded from access to basic services such as education, healthcare and formal employment.

In a society where access to public services requires ID authentication tied to one’s hukou, including mobile phone registration, e-payments and purchasing train tickets through China’s real-name system, this creates enormous barriers to daily life and increases the risk of long-term poverty and exploitation. This statelessness is thus more than a bureaucratic oversight, but a life sentence of exclusion. Human Rights Watch documents how families are forced to bribe officials, falsify paperwork or register children under another person’s hukou, as these half-North Korean, half-Chinese children live under constant threat of exposure in China.

COMPETITION AND EXCLUSION IN SCHOOLS

China’s education system is notoriously competitive, and access is strictly regulated through hukou. Even Chinese children with rural or out-of-district hukou face pressure to secure places in top schools, often requiring local residential status. For stateless children of North Korean descent, the barriers are nearly impossible to overcome. Without the means to escape that status, they are excluded from schooling altogether.

Even for those few who manage to leave for South Korea and reunite with their mothers, the challenges do not end. They face significant language and cultural barriers. Having grown up in China, many struggle with Korean fluency and adapting to South Korean society. They may fall behind academically due to gaps in schooling, face bullying or isolation due to their ethnic background and encounter mental health challenges tied to trauma, identity and belonging. Discrimination against North Korean defectors remains a persistent issue, and integration can be especially difficult for adolescents who have already endured years of instability.

ALTERNATIVE SCHOOLS IN SOUTH KOREA

Despite the many hardships, there are small but meaningful efforts providing hope and support for these children. In South Korea, a number of alternative schools have been established specifically to meet the needs of North Korean defector youth, including those who grew up stateless or separated from their families in China.

Yeomyung School, founded in 2004 in Seoul, is one such example. It serves middle and high school-aged students who have defected from North Korea or were born to defectors. The school provides a trauma-informed education that includes academic instruction, emotional support and life skills training. Many students describe it as the first place where they have felt safe and seen. Another example is Heavenly Dream School, founded in 2003 in Seongnam, which offers a holistic, Christian-based education focused on leadership development and personal growth. Built into a megachurch, the school emphasizes community living, with teachers residing alongside students in dormitories to create a stable, family-like environment. Over 90 percent of its graduates go on to higher education – a remarkable achievement given the challenges they have faced.

We’ve had a chance to visit both of these schools (see the amazing reunification Dan had with a refugee at Yeomyung School) and we were so impressed by the abundant love and care they poured out towards children who otherwise would also feel a similar statelessness even after arriving in South Korea.

The plight of stateless children left behind in China by North Korean defector women is one of the most heartbreaking consequences of forced migration and political oppression. These children are caught between borders, systems and national policies that deny them identity, protection and opportunity. Yet even in this bleak landscape, hope persists. With continued advocacy, support and compassion, more of these children can find a way out of the shadows and into a future defined not by abandonment, but by opportunity and care.